The ocean is scary. Humans are firmly terrestrial animals who aren’t particularly good at swimming, and the ocean is a whole planet full of water where you can’t see more than a few feet down. Anywhere you can’t see the bottom, there might be something underneath you. Humanity has spent most of its lifespan speculating just what those things beneath might look like, and of these, one of the most popular is the kraken. Only rivaled in sheer familiarity by the great sea serpent, the kraken is an octopus or squid of enormous size, popularly depicted attacking ships at sea and dragging them to the depths. The question we ask today is whether any animal we could call a kraken ever existed.

The kraken was not, notably, originally described as a cephalopod, or an aggressive animal at all. The earliest known description of the kraken comes from an old Norwegian educational text known as “The King’s Mirror“, written by an anonymous author in about 1250 AD to educate nobility on a wide range of topics, including the unexplained and marvelous phenomena of the world.

In a section dedicated to “whales” (which includes not just whales but some sharks and other large fish) the kraken is described as “more like an island than a fish” in size. It is described as exceptionally limited in number, the author suggesting that only two of them exist in the entire world, living near Iceland. They apparently feed by belching up their food, then swallowing the fish who come into their mouth to feed. Very little physical description is given of the animals beyond their great size.

The original kraken probably looked a lot more like this.

The first person to create the modern idea of a kraken as a massive cephalopod was probably Carolus Linnaeus, father of taxonomy. In the first edition of his massive work attempting to organize all life on earth into distinct categories, he described the kraken under the scientific name “Microcosmus marinus”, grouping it with squids and octopuses. This description, given in 1735, seems to have stuck in popular consciousness, even though Carolus Linnaeus himself cut the animal from future editions, deciding that it was likely mythical.

So because island-sized is excessive, let us define a kraken as a cephalopod significantly larger than the giant squid or colossal squid, the largest known members of their family. First, how big are they?

A live giant squid, 24 feet long. Tsunemi Kubodera.

Giant squid are the longer of the two, with a rocket-shaped body. They’re absurdly gorgeous creatures. Lovely deep red, huge, horribly human like eyes, and surprisingly massive tentacles. These tentacles form the bulk of their length, and that can be seriously impressive. The largest confirmed was only captured on film, measuring 43 feet long. Most are smaller, and top sizes tend to be around 600 pounds. Despite their size, almost nothing is actually known about giant squids. Their stomachs are usually empty when they get caught or wash ashore, so it is unknown what they eat. However, from the looks of the picture, they won’t ignore smaller squid if they get the chance to eat it. Notably, the largest giant squid found so far have been female, suggesting they are larger than the males, possibly so they can produce more eggs.

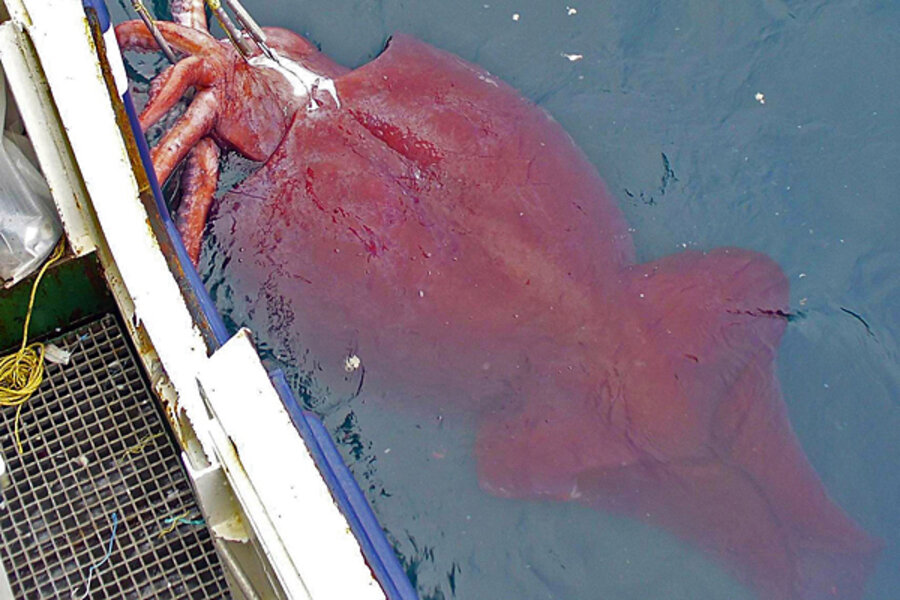

The colossal squid, a native of icy Antarctic waters, isn’t quite so rocket-shaped. If the giant squid was a formula 1 racecar, the colossal squid would be a dump truck. It’s a lot shorter than the giant squid, estimated to max out somewhere below 30 feet. Despite this, the largest of them, estimated from beaks found in the stomachs of sperm whales, could be up to 1,500 pounds. Those that have actually been seen haven’t been nearly so massive, but are still huge animals. Giant squids have rings of “teeth” on their suckers that often leave circular scars on the skin of sperm whales. Colossal squid instead have hooks on the ends of their tentacles, which likely serve the same purpose in immobilizing prey. They are thought to be slow-paced ambush hunters, floating in place to grab whatever prey comes near.

A colossal squid’s beak. Norm Heke.

The first question to tackle: are there any bigger living cephalopods, either members of the giant and colossal squid species or a species currently unknown to science? In short, it seems unlikely. There have been reports of giant squid larger than any officially measured, but they remain dubious at best. In 1887, a giant squid washed up in New Zealand was described at 55 feet, but this doesn’t match any modern finds (both those directly found and estimated from beaks found in sperm whale stomachs), especially given its mantle was only 6 feet long. Modern squid with similar mantles measure only 32 feet. It has been suggested that the tentacles were stretched, as they can be rather elastic after death.

Other accounts of exceptionally large squid have also proven to be fakes or misunderstandings. Above is a supposed 160 foot giant squid, which is rather easily noticed as a photoshop job even without the help of Snopes, who tracked down the original pictures this was spliced together from.

Other washed-up animals have also proven lacking. The Saint Augustine Monster is one of the most famous pieces of evidence for gigantic cephalopods, in particular a species of octopus bigger than any known to humanity, and is still used by some people to this day. The Saint Augustine Monster was a “globster” a relatively common occurrence where a heavily decayed animal or portion of one washes up on shore, leading to speculation about what it was in life.

Earliest photograph of the Saint Augustine Monster.

This globster washed up in Florida in 1896. It was first spotted by young boys riding their bikes by the beach, and was then referred to Dr. Webb, a local doctor who was interested in naturalism as a hobby. He declared it to be the remains of a giant octopus, based on the tube-like structures across its body, which he interpreted as severed tentacles. This was backed up at first by Yale’s Professor Addison Verrill, who named the animal “Octopus giganteus” based on photographs and speculated (read: pulled out of his rear) that it might have reached over 100 feet in length.

However, the octopus hypothesis fell through rather quickly. As soon as Verrill actually got his hands on a portion of the monster’s body, he declared it to be whale’s collagen rather than octopus muscle. Later studies proved him right, first a 1995 microscope study that compared the substance with whale collagen and then a 2004 study that proved conclusively that it was part of a whale. As likely the strongest evidence for a massive cephalopod in our modern era that we’re ever going to get, that leaves us looking to the past.

In the modern era, cephalopods without shells are the default. Octopuses and squids, the most well-known of our potential krakens, have nearly lost the shells of their ancestors, the only remnant a small piece of chitin called the pen that lies within their mantles, providing some protection for their internal organs. This and their beak are their only hard parts, and usually all that remains in fossils. And so, our first and most well-preserved potential kraken is a shelled animal.

Cameroceras and Endoceras were both orthocones, a form of nautilus relative with a long, straight shell instead of a spiraled one like a modern nautilus. It is uncertain which was longer, as most shells are not complete and we can only estimate the length of their soft tissues. However, modern estimates put the biggest among them between 18-20 feet, making them easily the largest animals alive in their time period, 200 million years before the dinosaurs. Being so huge, they were probably not the most mobile animals, focusing more on ambush. While there is a report of a 30-foot shell, it was never confirmed and seems to be one of those shady early finds of paleontology, never supported by further research. However, they were still longer than a modern giant squid if you don’t count the tentacles, and likely heavier by dint of their bulky shell.

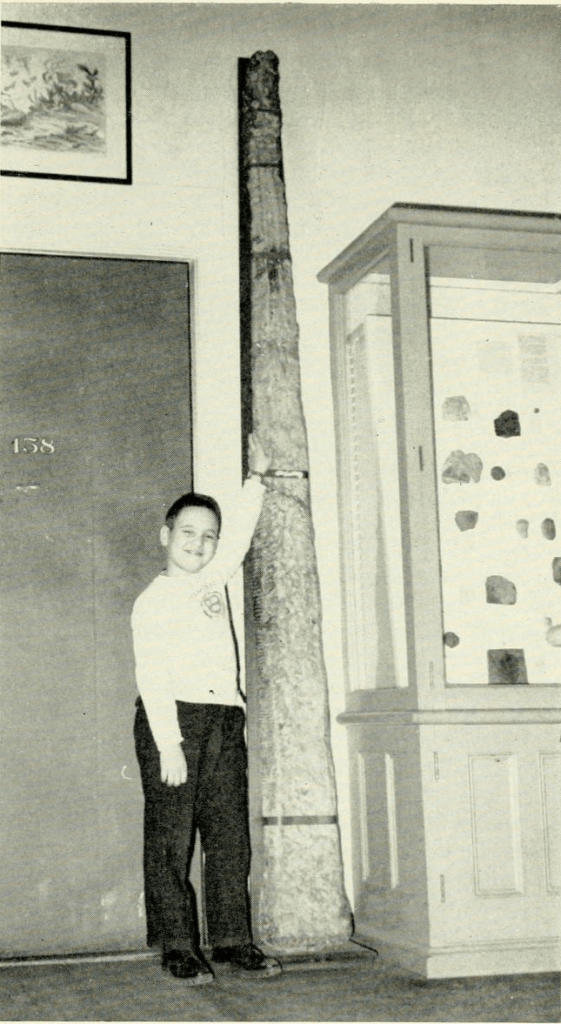

The largest ammonite, the missing portion of its shell reproduced with wire.

As the age of dinosaurs came on, the squids and octopuses began to come into being. However, their shelled relatives were still common, especially a group of spiral-shelled cephalopods known as the ammonites. These have a popular reputation as giant nautiluses, but this isn’t generally accurate. For one, they aren’t particularly closely related to the modern nautilus, rather being allied with the non-shelled cephalopods like squids and octopuses (and a million other less-known groups). For another, they had a wide range of sizes, some of them small, some massive.

Parapuzosia seppenradensis is the largest known ammonite and a pretty huge animal overall. Its exact size isn’t known because a significant portion of its shell was missing, but estimates range from 8 feet across to a whopping 11 feet in diameter. If you somehow straightened their shell, they would be 60 feet long, a giant squid and a half in length. Here we have an animal more massive than any modern cephalopod, weighing as much as 3,200 pounds, over twice as much as the weightiest estimated colossal squid. This was a huge animal, but was it the ravenous superpredator we expect a kraken to be? Well, not really. Even the biggest ammonites didn’t have the large, powerful beaks that modern giant squid do for tearing apart tough prey. Their beaks were rather weak, specialized for very small prey or even plankton. Effectively, they filter-fed. Peacefully drifting through the waves, just eating whatever met their tentacles.

So we had some success with the shelled cephalopods. What of those with no shells? The first cephalopods without shells begin to appear in the midst of the age of dinosaurs, about 100 million years ago. This was a tumultuous time in the oceans, known as the Mesozoic Marine Revolution, when many marine predators were taking on shell-crushing adaptations. It was like for millions of years everybody drove around in a tank and somebody suddenly invented the rocket launcher. A branch of cephalopods evolved drastically reduced shells, ignoring defense in favor of speed. It didn’t take long for giants to emerge.

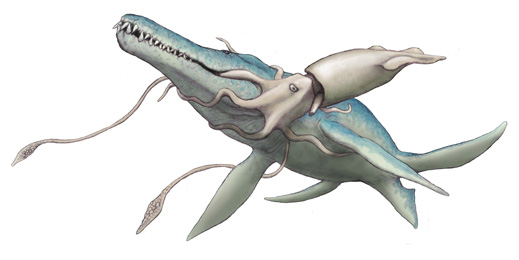

Most pliosaurs were actually the right size for this, so this might have actually happened. I’m so happy.

Yezoteuthis giganteus is a Cretaceous squid known only from two jaws, both found in Japan. As such, not a whole lot is known about it. Based on the size of the discovered beaks, however, it would have been roughly as large as a modern giant squid. However, it was found with the genus Inoceramus, a bivalve (similar to a clam or oyster, although with some much more massive species) which is mostly associated with the shallow waters of the North American inland ocean. This suggests that rather than a deep-dwelling species, these might have been giant squid you could see while waterskiing! Or whatever it is you people do at the beach.

If anybody can find who drew this, I’d be glad to link to them.

Tusoteuthis longa is another massive cephalopod from around the same time period as Yezoteuthis, although its taxonomy isn’t quite as clear. It is known from more than one pen, including a portion of one found within the stomach of a predatory fish. As big as Tusoteuthis was, there was a lot bigger in the water. Its exact mass changes depending on what you assume its body proportions to be, which varies greatly depending on what it is seen as closely related to.

Usually they are thought to be related to the modern vampire squid (which doesn’t drink blood and is more closely related to octopuses, so good job there). However, they may actually be even closer to modern octopuses and in fact be counted as the largest known octopus, or at least stem octopus (stem octopus meaning that their closest living relatives are octopuses). This would likely make them rather weighty, although likely shorter than the giant squid, given they would lack the long tentacles of a squid and only have an octopus’ shorter arms. And even then, they were hardly the most dangerous monster in their territories.

And, well, that’s about it for prehistoric krakens. We have a few mega-giants, but none of the whale-sized titans everybody wants. That’s kind of disappointing. Unless, of course, there really was a monster squid from the Triassic, so huge that it hunted whale-sized ichthyosaurs. A squid 100 feet long that acted not just out of hunter but the dark desires conjured up by an alien mind? Yeah, that would be a kraken.

Drawn by the awesome HodariNundu, check out their diving with sea monsters series.

The Triassic Kraken was proposed by Mark and Dianna McMenamin, and it sounds pretty impressive. And hey, something so radical must be really well-supported, right? Well, no. It’s not supported at all. This “kraken” isn’t based on a body found. No beak. No pen. Not even an impression of suckers. No, this was based on remains of the giant ichthyosaur Shonisaurus popularis. Often, they are found in large groups and nobody is sure why currently. It seems that not all of them died the same way, with some groups coming together after death and others all dying together. However, Mark and Dianna declared that the best explanation was that they were artwork, their bodies laid out on purpose by a giant squid trying to create self-portraits.

Of course, this isn’t exactly the most parsimonious explanation. No cephalopod today is smart enough for self-portraiture and there’s no reason to assume that a prehistoric one would be that much more intelligent. There was never a scientific paper on it because it wasn’t a scientific proposal that could be backed up by the available evidence. Sadly, there almost certainly was no Triassic kraken, or any other kraken. When it comes to our tentacled friends with soft bodies, the colossal squid might be as big as it gets.

Want more in-depth looks at prehistoric animals? Check out the following articles!

The original kraken makes me think of of all the giant turtles/islands that show up in anime. It would be cool if there were giant whale islands around, too!

A giant squid making a self-portrait does sound cool. If you told me an octopus did it, I might even believe you since they’re pretty damn smart animals. Don’t know if squids are also considered particularly intelligent.

In general, I don’t think that squid are usually as smart, but it’s hard to know. They’re a lot more focused on open water hunting, while octopuses crawl around on the sea floor and do a lot more exploration, so they at least come across as smarter.