My doodled takes on the American godzillas. One dinosaur, one Permian synapsid.

In 1954, something in a reptilian skin rampaged through Japan, leaving death and destruction in its wake. Nearly half a century later, a similar creature emerged in the USA. It looked quite similar, but under its skin, it wasn’t at all the same. It is well known that the original Godzilla movie invoked the horror of the nuclear bombs, and just as clear that as Godzilla became a more ambiguous and even heroic figure, this angle was toned down. The fact that Godzilla was mutated or at least awoken by nuclear testing remained, but it became more of a superhero origin, not a defining trait of the character.

I personally haven’t seen enough of Godzilla’s Japanese movies to track the evolution of its themes over time. No, what interests me today is how those themes have changed with an American perspective. For the purposes of this article, I’m only concerned with the Monsterverse films, not the 1998 Godzilla. The Monsterverse has three Godzilla movies for me to work with, and it establishes a much more unique and even slightly bizarre thematic identity for itself than the 90s film does.

Part One: Godzillasaurus

A depiction of the dinosaur Gojirasaurus, named after our famous kaiju and drawn by Nobu Tamura

First and foremost, the Monsterverse’s Godzilla is natural. It was not created by nuclear testing, but is instead naturally a radioactive behemoth. This seems minor, but it changes a core element of the character, one kept even by the 1998 version. Godzilla in the Monsterverse is no longer an aberration, a nuclear mistake, but a natural creature, one that has been around in its current form for a very long time. This more naturalistic angle is heightened by the fact that the kaiju form an ecosystem of their own. The monsters that Godzilla battles in the film supposedly kill members of zilla’s species and bury them with their eggs to provide sustenance for the growing young.

So that is our baseline for the Monsterverse. Godzilla is a natural creature, with naturalistic motivations. Godzilla seeks to destroy the MUTO because they are its natural predators and rivals, not out of either a greater motivation or mindless destructive tendencies. Godzilla is effectively an animal, albeit an animal of breathtaking scope and power. It wasn’t even clear yet if it was particularly more intelligent than an average animal.

In this chapter, there is still a great question of whether Godzilla is necessarily good for us. The MUTO were worse for humanity, what with their tendency to reproduce quickly and destroy electronics with their EMP ability, but there was an ambiguity to Godzilla. It was a giant monster that ate radiation, that could lead to plenty of problems if, say, it ripped open uranium mines around the world. In a lot of ways, this situation was not dissimilar to most of Japan’s Godzilla movies. Godzilla would fight other kaiju (Titans, in the Monsterverse and the rest of the article) that it saw as rivals, but it wasn’t on our side and caused plenty of collateral damage when it did.

Things would become stranger when King of the Monsters came out and we got a larger look at the world of the monsters.

Part 2: God

The titans kneel to Godzilla at the end of King of the Monsters

King of the Monsters seems like it wanted to follow the path of the 2014 film in making Godzilla part of an ecosystem, but the plotting and themes of the movie change the context of the character in some truly bizarre ways. An example that cuts both ways is the use of communication. Godzilla uses flashes from its back spines as a threat display early on, a very animalistic form of communication. However, we also learn that the various titans communicate with one another via subsonic rumblings. This wouldn’t be so strange, but for that every single titan, no matter how divergent in form, can speak to every other titan. All titans use the same language to communicate, regardless of species.

The other major addition we get to the lore of all titans is their new, deeper tie to nature as a concept. The areas where they rampage grow back thicker with plant and animal life than they had before. This point is made in the movie proper, with the parts of San Francisco that faced the brunt of Godzilla’s fight with the MUTOs becoming covered in thick vegetation, but is reinforced in the credits. The radiation Behemoth gives off reforests the Amazon, and Scylla gives off chemicals that slow the thawing of the polar ice caps.

On the one hand, large animals do actually shape their environments in many ways. Elephants can change the density of tree growth in wide stretches of the savanna. However, this is still unusual for two reasons. One, it presents environments as something permanently stable, held in stasis by the titans. Two, these animals predated the Amazon rainforests and the polar ice caps even existing. Nature is, apparently, something eternal and unchanging, not a chaotic, loose concept hard to nail down.

The concept of a monster ecology continues to break down the more is revealed. What makes Ghidora such a threat isn’t merely his own individual power, it is his ability to command the other kaiju through the use of this language. This ability isn’t an aberrant one caused by Ghidorah’s alien nature; it’s actually the native role of Godzilla’s species. Godzilla has dropped all pretense of being any sort of regular animal and is now an actual ruler, or even a straight up deity. Mothra’s defense of Godzilla is presented as a symbiotic relationship, but she gains nothing from it and dies in helping him. She isn’t an animal with a special relationship with Godzilla, she’s a vassal to a king.

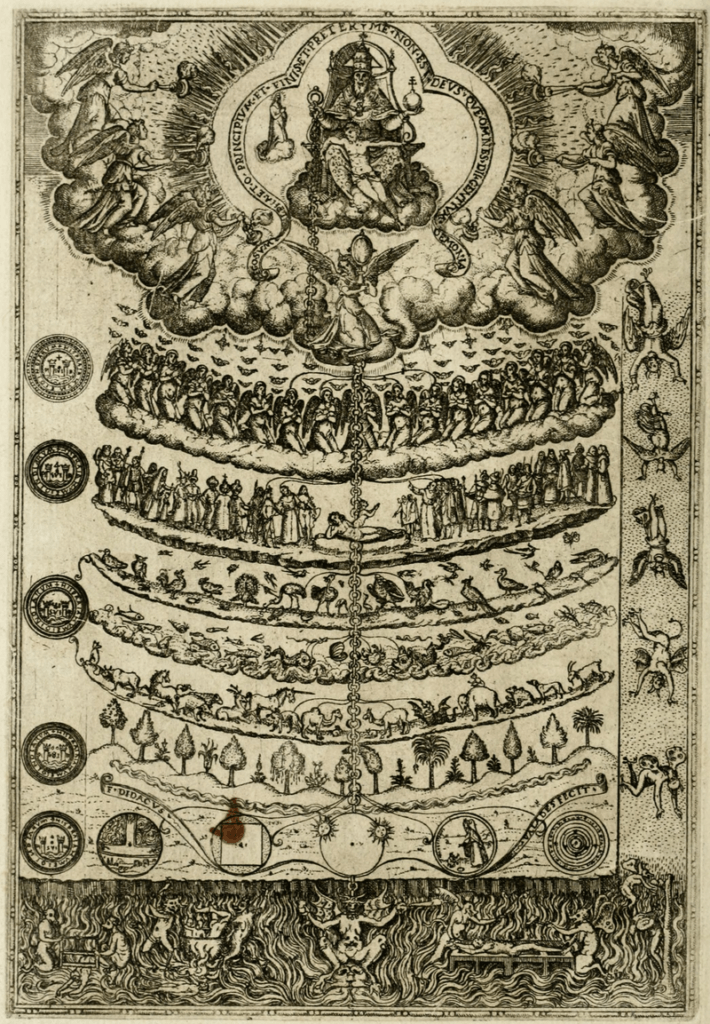

A depiction of the Great Chain of Being by Didacus Valades

Gone is the modern concept of nature as a flexible ecosystem, a complex food web that humanity is part of. What the Monsterverse’s conception of the natural order reminds me of most is an ancient philisophical concept, the Great Chain of Being. Originally posited by Greek philosophers and refined in the middle ages, this posited the universe as a stable hierarchy, with God at the top as creator and ruler of it all, his angels as his agents, then humans, animals, plants, and last minerals. It fits in with a distinctly static understanding of the world that fits the Monsterverse; it doesn’t matter that Godzilla is a creature displaced by hundreds of millions of years, its place remains stationary. Kong can fight it for that place, because there is a throne to occupy, not just an ecological niche.

The Monsterverse Godzilla, under the exterior of some very simple and extremely stupid movies, has formed a complex thematic identity for Godzilla. As an embodiment of an ordered nature, Godzilla presents an ordered universe that is, as a whole, benevolent to humanity. Without any explicit religious themes, the Monsterverse shows us a surprisingly Christian universe, where humanity is important enough to be worth protecting by greater beings and not just more small animals to be ignored and stepped on, and the Big Guy is on our side. Godzilla, finally, seems to be a god.